Harry Leigh-Dugmore was evacuated from Dunkirk as part of Operation Dynamo in May 1940.

This is his remarkable story.

We were ill-prepared for the events of May 1940.

Despite inventing the tank, which revolutionised warfare, our thinking and training were still too firmly based on the idea of two opposing armies in holes in the ground.

We spent the first eight months of the Second World War digging holes in the ground to extend the Maginot Line to the Channel coast.

Then, when the Germans poured into Belgium, instead of sitting in those holes and going bang-bang when the Germans got there, we drove on through Belgium to meet them - to the welcome and temporary delight of the Belgians.

But we could not hold them and started falling back.

From somewhere near Louvain we began driving in convoy towards the Channel coast until the Military Police stopped us at a crossroads to allow movement the other way.

We had been given no information about where we were going other than to follow the vehicle in front.

But, when we were allowed to continue we had no vehicle to follow. Looking backwards, I could see that I was in the leading vehicle of a convoy of two.

When, after some time, we had not caught up with the vehicle we were originally following, we stopped for a council of war.

None of us had any idea where we were supposed to be going.

This revealed that we were a fighting unit comprising one Lance-Corporal and eight other ranks with a variety of small arms and assorted stores mounted on one 15 cwt truck and one Bren carrier.

None of us had any idea where we were supposed to be going.

The other conclusion was that the Lance-corporal was in charge and was expected to do something about it.

I was that lance-corporal: then a youngster of 20 summers, only two of which had happened since I was a schoolboy. The others were all older than me.

Suddenly, without any warning or preparation, I was in charge of people who just happened to be there at the time.

My recollections of the next two weeks or so are of a disconnected set of events.

One day we found a quartermaster's truck that had been abandoned. None of us had had a bath or even a good wash for at least a week, so we stripped at the side of the road and re-dressed ourselves in brand new underclothes and shirts - wonderfully refreshing.

We helped ourselves, too, to his stock of bully beef and had a tin each to eat then and there. But even after about three days with nothing to eat we could not manage a whole tin each.

On a search such as ours you have to travel with your eyes and ears wide open. So we moved by day and laid up at night - in barns when possible - and got what information we could from other troops and from the locals, but not much because ignorance reigned supreme.

With no maps and no knowledge of the terrain we could often only take our direction from the refugees. They too were moving away from the Germans but sadly and forlornly and there was nothing we could do to help them.

At night, if we felt sufficiently clear of trouble, we took off our trousers and boots. One evening, though, I thought us less secure and gave an order that no boots nor clothes would be removed and that we would take it in turns to be on watch for an hour each so as to give the alarm if a swift departure seemed appropriate. The British soldier hates keeping his boots on when he is asleep but that particular night they all kept them on without a murmur.

Looking back, I see now that this was the point when I realised that I had come of age, as it were, and that my group had accepted that I was in charge and could make the decisions. I felt now that I had earned my stripe. By the time I married, three months later, I had three stripes and eventually three pips.

We found our battalion eventually but most of them didn't know who I was, where I'd come from, or why I was there.

Evacuating from Dunkirk

We queued for the best part of two days for boats coming to the mole. When German planes came over bombing and machine gunning we spread out as far as possible but sportingly returned as nearly as we could to our position in the queue.

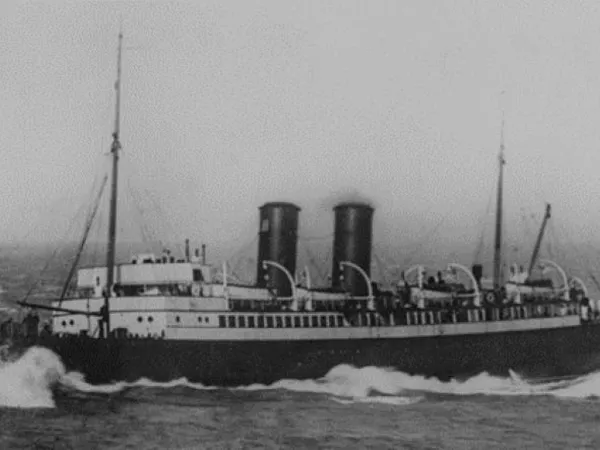

Eventually we boarded the Maid of Orleans, in peacetime a cross-channel steamer but now it was pretty well standing room only.

We sat on the deck for'ard around a pair of Lewis guns mounted on a stanchion and tended by a bombardier RA.

We loaded his magazines with one tracer to every five ball to give the approved 'hosepipe' effect. He brought down a Messerschmitt and we callously cheered as it crashed into the sea.

We cast off from the mole at 0600 and tied up at Dover at 0900 - a long trip to circumnavigate the minefields.

We got onto a train straight away and were off - to Aldershot, somebody thought - but I awoke at ten past midnight to find myself at Brecon in mid-Wales.

Dunkirk was a time when the British skill at improvising shone brilliantly.

Dunkirk was a time when the British skill at improvising shone brilliantly: civilian as well as Naval vessels gathered from far and wide for the channel crossing; several hundred railway trains were produced and filled with troops at channel ports to be distributed throughout UK; barracks were ready to receive them, feed them and sleep them; women's organisations manned railway platforms to provide food and drink as trains passed through.

And the final touch? Welsh pubs open on a Sunday, supplying beer and refusing to take payment for it.

Harry Leigh-Dugmore passed away in 2020.