80 Years On...

There have been 80 summers since the end of the Second World War. We honour the men and women of the generation who served with specially-commissioned portrait photography by Steve Reeves.

Each was an eyewitness to astonishing times. Their gaze captures the spirit of the generation who won the freedoms we enjoy today.

These images remind us that peace was won only by the collective efforts of millions of people from all walks of life, and from all corners of the globe. Join us in remembering their service and the sacrifices they made.

Ralph Ottey

"When I was 16 I wanted to be at Churchill’s right hand!" explains Jamaican-born Ralph Ottey. So, in 1944 he joined the RAF and travelled to Yorkshire, via the USA. At Filey the 13-weeks of training was gruelling, and he was then assigned to 617 (Dambusters) Squadron.

He became the chauffeur to a senior officer and witnessed the reality of war when aircraft failed to return: “The camp mourns because we are all in it".

Ralph was training to be an Air Gunner, a role he had dreamed of, and to be deployed to the war in the east when news broke of Japan’s surrender. After the war Ralph became a successful businessman, and notable cricketer, in Lincolnshire.

"What I learned in the RAF has stood me in good stead all through my life… I was ready to play my part, I volunteered. I don’t regret it, I don’t regret one minute of it. It changed my life."

Doug Baldwin

Doug Baldwin was conscripted into the King’s Own Scottish Borderers and was 19 years old when he landed in Normandy shortly after D Day, 1944.

“I felt like a hero then, everyone was waving to me and blowing kisses.”

He was a Bren gunner and saw repeated action on the front line until August when, dazed by a shell burst, he was captured. Taken to Germany, he spent nine months in a prison camp and put to work on an open cast coal mine and on railway lines. “You’d pack the line with gravel or sand. As the trains went over, the line used to sink, we’d have to keep it as level as possible.”

Doug and his comrades woke one morning to find that the German guards had abandoned the camp. After help from American troops, he was flown back to Britain shortly before VE Day. “The sun was just coming up and I could see the White Cliffs of Dover… I’ll always remember that.”

Joyce Wildling

Unbeknown to her parents, 18-year-old Joyce was interviewed to enter the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry. The secrecy continued when she was assigned to centres where Special Operations Executive (SOE) agents were trained. “We only knew them by a code name, so it was never their real name, because they had to get used to their new identity.”

At first, Joyce was a Transmitter Hut Attendant, receiving messages from agents in occupied Europe. Sometimes transmissions would abruptly cease: “That was the worst thing, really, one could do nothing about it. We never really spoke about it, you know, we just looked at each other and it went, you know, dead.”

On VE Day Joyce and her comrades “went to Piccadilly where there was a stream of people singing and dancing; we joined a crocodile and did the Palais Glide down Piccadilly; there were soldiers up lampposts, it was extraordinary.”

Yavar Abbas

Yavar was a student at Allahabad University when war was declared. As a Nationalist he was incensed that Britain had declared war on behalf of Commonwealth countries, yet he recognised the global threat and joined the 11th Sikh Regiment. Frustrated with his posting in a “garrison battalion” he seized an opportunity to train as a combat cameraman.

Armed with a camera and a jeep, Yavar was soon documenting the brutal reality of war, from the aftermath of Kohima to major battles in Burma. "I climbed on a tank roof once during the fighting," he recounts. "The tank commander opened the hatch and put me in my place – on the ground!"

The risk was great: "A Gurkha soldier was shot next to me, dying right there. It could have been me."

He was in Delhi on VJ Day and later filmed in occupied Japan, including Hiroshima. Later, he moved to the UK and became a renowned writer, filmmaker and advocate for peace. "War is the real crime. If there is no war, there'll be no war crimes.”

Dorothea Barron

To join the Women's Royal Naval Service, Dorothea 'Pixie' Barron cleverly overcame their height restriction. “I cut out cardboard heel shapes and put those in the heels of my normal shoes, to lift me up a bit, and I fluffed up my hair as high as I could get it.”

Her excellent eyesight made her a natural at signalling, and she became proficient in Morse code and using signal lamps and semaphore to communicate with ships. “You had to question a ship as it appeared, to see if it was the enemy or if it was friendly.” Dorothea's training also led her to play a crucial role in the D-Day preparations.

Dorothea recalls VJ Day and spending it in London with her boyfriend (and future husband). In peacetime, Dorothea was frustrated that women’s opportunities in civilian life again were restricted, but she reflects: “People suddenly realised, good heavens, women have got brains.”

“I learned that I could tackle anything that arrived, anything that arose, any problem. There was always a way to tackle it.”

Brian Latham

On his 18th birthday, Brian Latham asked the accountant at the bank where he worked, "Can I have half an hour off? To go and join up."

Brian trained as a pilot in the UK and the USA. After heavy losses of pilots at Arnhem, Brian volunteered for the Glider Pilot Regiment. In March 1945, he flew a Horsa glider across the Rhine into enemy territory in Operation Varsity, the largest airborne operation of the war.

“We were the first squadron across; at 2,500 feet, we flew into flak. A shell blew up in the cockpit… so we had no flaps. We were coming in like a bat out of hell, over 100 knots.”

Despite losing the nose wheel to enemy fire, Brian landed and the cargo of troops and a jeep were unloaded. They then held their position for three days, repelling constant German attacks.

Back in the UK on VE Day, “I hitchhiked with a pal of mine up to Shrewsbury, my hometown… we had great celebrations in the square, and I met a lot of people I knew.”

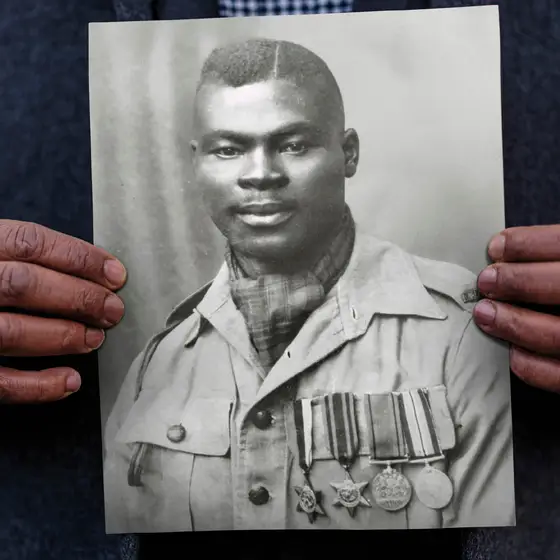

Michael Kofi Adjivon

Born in Togo, Michael moved to Ghana (formerly The Gold Coast) at the age of six.

At 18, he joined the 81st West African Division and served as a signaller in Burma. A skilled swimmer, he was selected for reconnaissance missions along the Kaladan River and fought with the infantry to halt the Japanese advance at Myohaung. After the war, he re-enlisted and achieved the rank of Regimental Sergeant Major.

Michael built a house in Accra called ‘The Barracks’, filled with artefacts from the war. A plaque on the wall includes his words: ‘It is courage and determination that wins a battle... Brace up, chest out, stride out briskly and close the gap’.

His dedication to his fellow veterans continued until his passing in 2006. He is remembered by his grandson, Mensah. "He was front and centre of a number of Veterans Associations... so I can only imagine this was the space in which he felt most comfortable reflecting on his experiences.”

Anne Eddleston

Anne Eddleston was called up on Christmas Day, 1942, “I thought it was a late Christmas card. It wasn’t until later, that I realised.

She became a Women's Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF) wireless operator, volunteering for Egypt. At a welcome reception, fate intervened, "As soon as I walked in a handsome young man offered to buy me a drink. When I asked for a lemonade, everybody laughed." That light-hearted exchange with Bill began their love story.

Never one to shy away from a challenge, she volunteered for Cyprus: "We flew over, lying flat in the fuselage of a small plane. I had never flown before, so that was a challenge."

Bill returned home first, and they married upon her return in October 1946. "I came back a changed person… so it was hard to settle back into civilian life."

"I never wanted there to be another war. I think we never learn... I worry that youngsters don't know or care about the war."

Rajindar Singh Dhatt MBE

Rajindar joined the Indian Army in 1941 and was promoted to Havildar Major (Sergeant Major) before being deployed to northeast India, followed by the gruelling liberation of Burma in 1945.

“We supplied rations and water, ammunition, everything to the front forces. It was our duty to keep them fully equipped. Sometimes they asked us ‘are you afraid?’ We tell them we have come voluntarily in the army, and we came for fighting… Bullets are coming on, machine gun, Bren gun, that was normal for us. The Sikh army was very strong.

“We were very happy when on 15th August the Japanese surrendered and we said, ‘Thank God, we have won the war’.”

Rajindar came to the UK in 1963 and trained as a welder, before settling with his family in Hounslow and helping found the Undivided Indian Ex-Servicemen’s Association. “It was a great help from the Commonwealth countries... So many people killed; thousands of our soldiers, they gave their lives”.

John Westlake

Leading Aircraftsman John Westlake’s job was vital: maintaining the weapons of the aircraft in his charge. The 20-year-old oversaw a team that followed the front line across Europe. In May 1945 they reached an airfield at Lingen in Germany. “There were five American bombs still sticking in the ground. They'd already been defused by the army. And we parked our tents there.

“The announcement then came that VE Day would be at a certain time, and we were issued with a mug full of rum. We'd never tasted rum in our lives… And we started singing… We woke up with the dawn the next morning - soaking wet, covered in dew, and, well, we were feeling cold, so we thought we'd got to get warm. Someone suggested getting the Luftwaffe wooden huts into a big bomb hole, to set fire to them.

“And we all sat around there getting warm again. There was a sense of relief amongst us all that, finally, the killing would stop.”