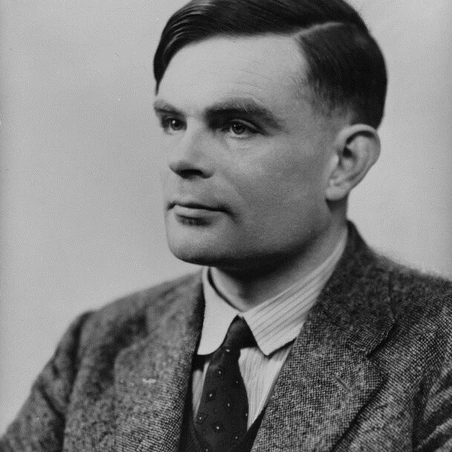

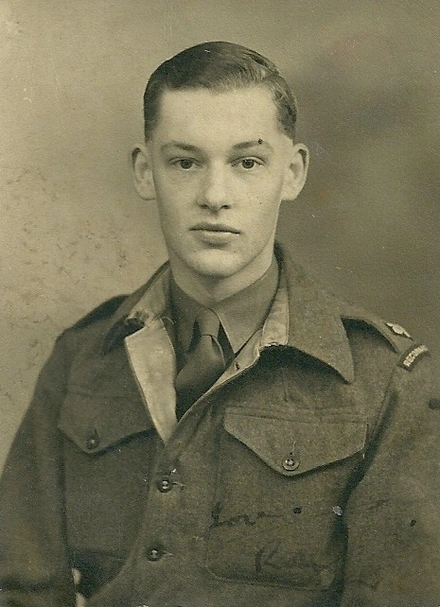

Roy Cockburn left school at 18 to join the army. Three years later he was a Second Lieutenant leading patrols behind enemy lines at Normandy.

In late 1941, I left school at the age of 18 and joined the Green Howards. I had forsaken my medical studies at Nottingham University, much to my parents’ displeasure, but after basic training and Service in the UK, I was recommended for officer training at the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst.

I attended the centre between January and October 1943, graduating as a Second Lieutenant on 31 October, aged 20.

After passing out, I joined the 43rd (Wessex) Reconnaissance Regiment and commenced training for what would be the Normandy landings in June the following year. We were billeted near Eastbourne and trained extensively in the local area to prepare for our recce missions in France.

On 18 June 1944, 12 days after D-Day, my squadron boarded the MV Derrycunihy – a cargo ship that had been converted into a military transporter – in London’s West India Docks.

We set sail for Sword Beach, which, after joining a convoy at Southend-on-Sea, we reached two days later.

High seas and enemy shelling prevented our unloading for three days, so, on 24 June, the ship moved along the coast to Juno Beach. I happened to be on deck early in the morning and as the Derrycunihy started her engines, an acoustic mine beneath her keel exploded, splitting the ship in two.

Fortunately for me, I was at the front of the ship, but the rear sank rapidly – trapping countless men below in their sleeping quarters.

Looking down and seeing all the bodies in the water is a memory that has never left me.

We took those that survived to shore to have their wounds treated, but we lost 183 men in total from 43 Recce as well as 25 of the ship’s crew, which turned out to be the biggest single loss of life off the Normandy invasion beaches.

The following day, I went back aboard with my men to salvage what we could from the wreckage, getting vehicles onto a pontoon in preparation for our landing proper and the start of our recce patrols.

On two separate occasions I had to take a patrol behind enemy lines on a recce mission.

On the second occasion, we came under fire from machine guns and the soldier nearest to me was shot in the head.

The enemy sent up flares, exposing our position, and started to mortar us.

Having gathered sufficient information, I managed to crawl back 200 yards in open country under continuous fire with the wounded man to our fallback position, from where the soldier was evacuated.

I was awarded the Military Cross for my actions, with the citation reading, “He showed great powers of leadership and by his coolness and determination, valuable information was gained.

Throughout he showed a complete disregard for his own safety and was an inspiration to the men under his command.”

I didn’t think of the danger at the time. I was concentrating on returning with my soldier.

The soldier wrote to me some months later thanking me for saving his life, but I never met him again or heard from him after the war.

I didn’t think of the danger at the time. I was concentrating on returning with my soldier and ensuring that HQ was made aware of the enemy’s strength.

I remained in Germany after VE Day and saw the displaced persons of Bergen-Belsen – prisoners had lived in appalling conditions at that concentration camp, without expectation of help from the British – before being promoted to Captain in January 1946 and posted to India.

I returned to the UK in 1947 and served in the War Office until my retirement from the Army in 1950.

In more recent years, thanks to the work of my local Legion branch [Canterbury], I have been awarded the Légion d’honneur.

The French government decided that it would honour all British Normandy veterans, with my award in recognition of my services to ensure the liberation of France.