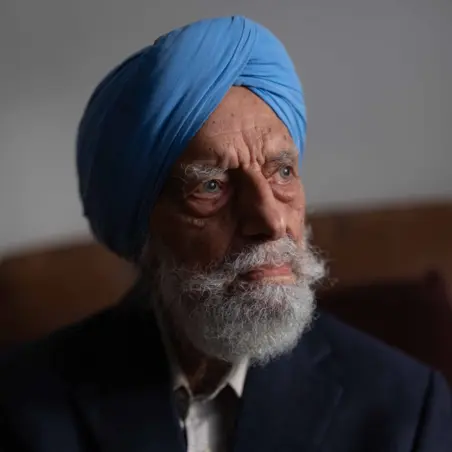

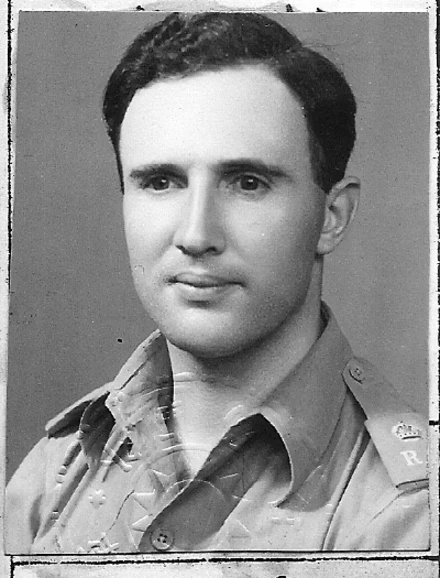

After the fall of Hong Kong, Major John Monro was one of thousands of Allied troops taken as Prisoners of War by the Japanese. This is the incredible story of his escape and journey across China.

In February 1942 Major John Monro escaped from a POW camp in Hong Kong with two colleagues and made his way across China to the administrative capital at Chongqing, 1,500 miles away.

They travelled on foot, by truck, train and boat and eventually arrived in Chongqing two months after they had left Hong Kong.

All three men were awarded the Military Cross for their bravery.

Using her Father’s diary entries and letters written at the time, John’s daughter Mary has retraced his journey.

The battle of Hong Kong

A fierce battle raged for over two weeks. The New Territories were poorly defended and quickly fell, leaving only Hong Kong island in the hands of the Allies.

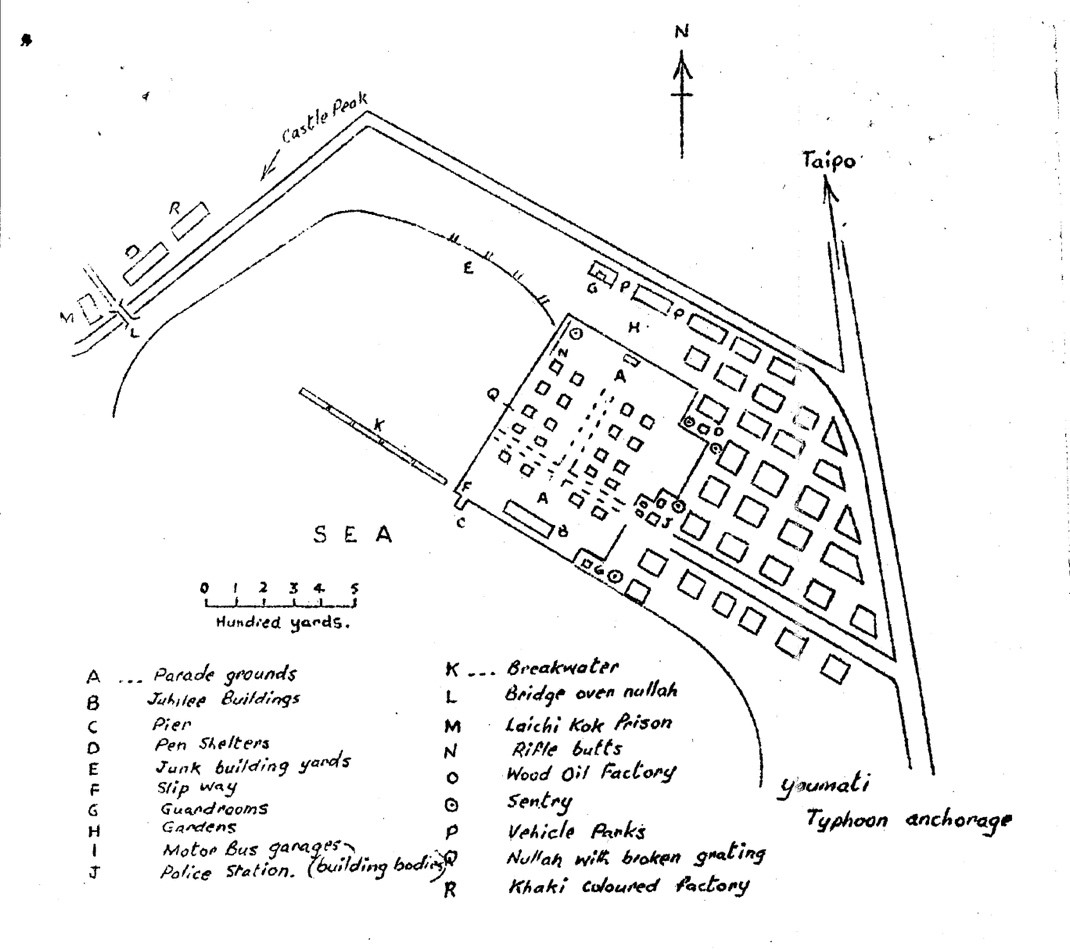

By Christmas Day the battle was lost and within days troops were marched across to Kowloon and imprisoned at Sham Shui Po.

Planning the escape

John Monro regarded it his duty as an officer to attempt to escape.

Over the next few weeks he made plans and gathered two fellow officers who were prepared to join him, Flying Officer Baugh (later killed in action in Burma) and Captain Trevor, who spoke Cantonese having worked for the Kowloon-Canton Railway.

There were many potential obstacles to consider:

“By going to Sham Shui Po one great obstacle to escape (the crossing to the mainland) would be behind us.

"Should I take food across in the hopes that I would be able to make a quick getaway, or should I take clothing in preparation for a long stay?

"I was undecided and made a compromise. I took a little food but a lot of clothing.”

The date for their escape was set for the evening of 1 February 1942, coinciding with a full moon to facilitate night travel.

The men gathered food, medicines, a compass and some cash and made a raft to carry their supplies as they walked out of camp along a submerged breakwater. They then had to swim across the bay, which took almost an hour.

A sketch of Sham Shui Po POW camp in Hong Kong

A sketch of Sham Shui Po POW camp in Hong Kong

For the next five nights they made their way through the hilly terrain of the New Territories. Progress was slow and difficult, but at least they were in familiar territory.

“After a couple of hours two Chinese arrived; one with a bad tempered and shifty expression who appeared to be the leader of the gang, the other spoke English and had been a steward on a British Freighter and knew Liverpool well. For a time they refused to believe that we were escaped prisoners but thought we were Japanese spies.

“They refused to believe that we had swum out of camp. ‘How is it’ they asked, ‘that your packs and clothing are dry?’ We explained to them that we had carried them on a raft, but they could not believe that the Japanese would allow us the opportunity to build such a thing. They were only convinced when they found that the shorts in our packs were still wet and tasted salt.”

Into China

The party walked north along the railway and once in contact with the Chinese forces, they were given help, accommodation and food.

They arrived in Waichow on 12 February, shortly after the town had been razed by the Japanese, who had terrorised or murdered the inhabitants and left just three days before.

Their arrival coincided with Chinese New Year, which was celebrated as usual, delaying their progress.

From Waichow they headed for Longchuan, travelling by boat and sampan up the East River. And from Longchuan they headed for the wartime capital of Guangdong province, Shaoguan, this time by truck.

"Trucks are few are far between in China. Though the magistrate was helpful and sympathetic, the official in charge of transport was a fat, self-important nit wit. When we did get a bus it was a closed truck with two small windows on either side, one behind and one in front with a completely closed back. Inside it was almost 5 feet high. Into this enough luggage was put to cover completely the whole floor to a depth of two feet. Into the space above we crammed 34 people.

The drivers were very unwilling to unlock the rear doors, partly because it was a rather long process and partly because at every opportunity we would jump out to stretch our aching limbs and it took a very long time to put us back in again. To add to our comfort about 50% of the other passengers were constantly car sick.

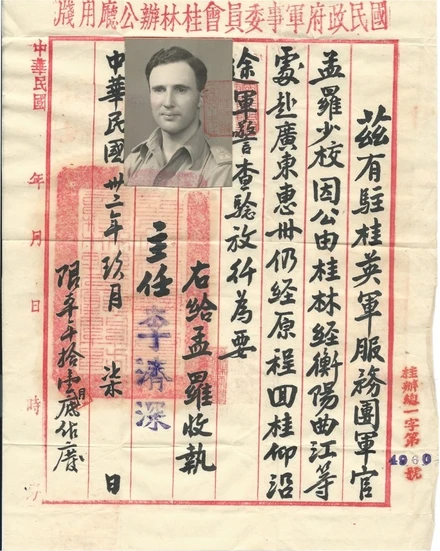

They continued by train to Guilin (via Hengyang).

Here they met the Chinese Marshal in command of a large part of the Chinese army, who supplied them with passes to travel on to Chongqing where they finally arrived on 31 March, two months after they had left Sham Shui Po.

John Monro was sent to India for an appendectomy and then returned to Chongqing in August 1942 as Assistant Military Attaché.

He spent the next 18 months supporting and trying to liberate the POWs he’d left behind in Hong Kong. In July 1944 he was sent to Burma to fight the Japanese, eventually returning to England in early 1945.