Bill Harrison flew Beaufighters during the Second World War. He talks about crash landing, taking fire, and the comrades he lost.

When the Second World War broke out I was working on the family farm near Skipton; I was also a Lance Corporal in 2nd/6th Battalion, Duke of Wellington’s Regiment.

When mobilised as part of the BEF [British Expeditionary Force], we went initially to St Nazaire, France. After a while, we were taken by train to the front.

We were bombed by Stukas during the transfer; I’ll never forget that ‘siren’ noise. At the front we were in contact and the Battalion lost four or five men.

The only good thing about the journey was the bottle of whisky we had acquired from some NAAFI.

In May 1940, we were told ‘every man for himself’ and to make our way to Cherbourg. We walked by night and laid up during the day; it took around five or six days.

We were on the last boat out of Cherbourg; it was crammed with British and French troops – the only good thing about the journey was the bottle of whisky we had acquired from some NAAFI [Navy, Army and Air Force Institutes] stores.

We knew nothing about Dunkirk until we arrived in Southampton the next morning.

Flying Beaufighters in Libya

On returning I wanted to do something different, so I joined the RAF as a pilot. After flying solo in a Tiger Moth within the required 12 hours, I sailed to Winnipeg, Canada in late 1941 to train; I had to learn how to navigate as well as pilot planes.

The training took about 14 months, and I sailed back to the UK aboard HMS Queen Elizabeth.

After six months on the Scottish island of Islay, I converted to flying Beaufighters and flew to join my unit – 603 Squadron – in Gambut near Tobruk, Libya.

On the first leg, the wheels stuck and I had to crash-land; eventually I made it to North Africa and was there for the rest of the war.

Our role was to attack enemy shipping – we had four cannons, one machine gun and eight rockets.

On one occasion, an enemy bullet went through the hydraulic pipe beside my leg and oil spurted straight onto the windscreen. I wiped it off before taking emergency action to avoid the funnel of an enemy ship.

“I couldn’t get any answer from Jim, so I alerted the airfield and an ambulance was there to meet us.”

I had to make my second crash- landing on returning to base: the propellers hit the ground first at about 110mph and we stopped within 40 to 50 yards.

My navigator was Jim Dibbs – he and I got on well and were very close. In August ‘44, we attacked a ship and they were firing back at us.

On the way home I couldn’t get any answer from Jim, so I alerted the airfield and an ambulance was there to meet us. Something had come through the perspex canopy, and he was already dead when we landed.

He was a young lad – only 22 – and is buried in Acroma in Libya. He was an only child; I visited his parents after the war and they were devastated.

The CO loaned me his navigator, but on our first sortie he got an incendiary bullet through his shoulder. I wasn’t the most popular pilot in the squadron at that point!

Quite often I came back with several holes in my fuselage, but on one day there were a few more.

The recce reported a 13-ship convoy; by that time the Americans were with us and the plan was for them to go first and bomb the ships to disperse them, so that when we attacked the firepower would be less concentrated.

When we got to the target area, the flotilla was sailing along – the Americans hadn’t been able to find it. The firepower at us was horrific, like flying through a hailstorm.

We lost seven of our 24 planes, I had 27 holes in my fuselage and the rocket rails were damaged. However, we managed to sink 12 of their ships and got the last one the following day.

I honestly didn’t ever think I would be killed in combat. But every time I went up, I prayed that the Lord would look after my wife, Inez, if I didn’t come back.

I didn’t really think too much either about the crews of the enemy ships – it was long-distance engagement, and it was them or us. There were a few times, though, when I was glad I was not in their position!

After I was demobbed, I went back to Yorkshire and saw my daughter for the first time. I never spoke to my children about my experiences; I didn’t think they would be interested and to be honest, I didn’t want to look back.

On reflection, I suppose I suppressed the memories. However, when my grandchildren started asking me questions, it all came out.

I always remember Jim and the others we lost, and lay a cross at my local war memorial every year. I was lucky to survive the war, and have been very fortunate in life.

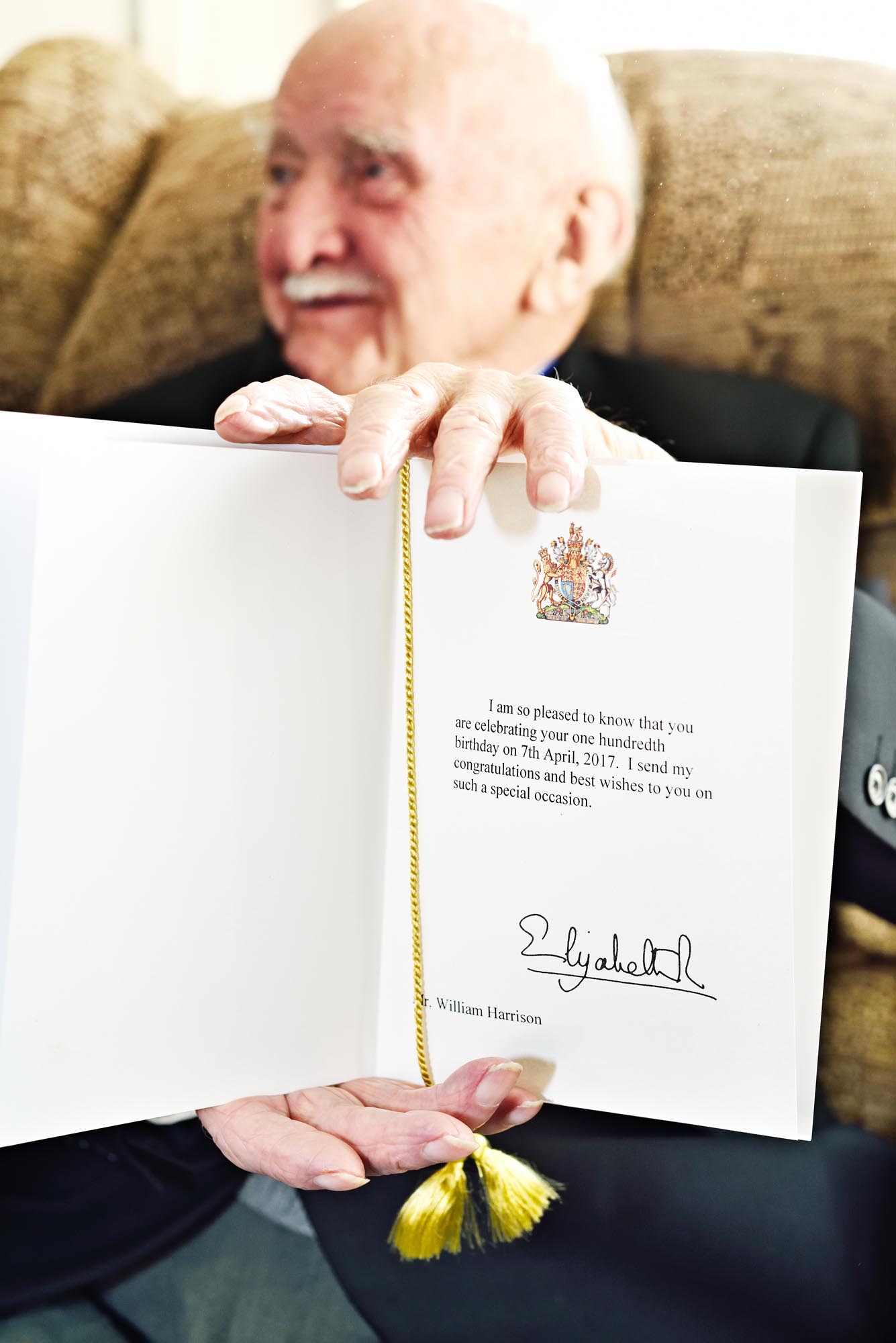

In April 2017, I received my 100th Birthday Telegram from the Queen to go with the Diamond and Platinum Wedding Telegrams that Inez and I had also received.