It’s 25 years since the ban on LGBT serving personnel in the Armed Forces was lifted.

Following in her grandfather’s footsteps

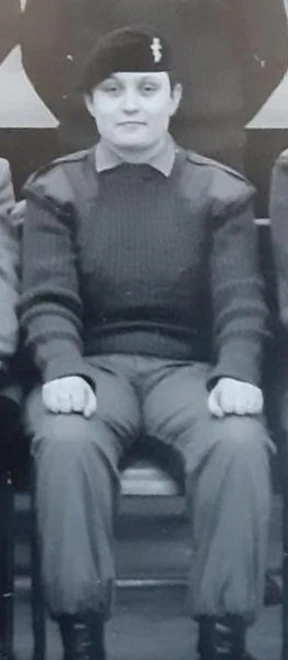

Marci was born in 1973 and grew up just outside Scunthorpe. Her grandfather, a former Royal Electrical Mechanical Engineer (REME), was a strong influence in her career choice. “I was very interested in motorbikes, go-karts. I learned a lot from

him. He was always showing me how things worked.”

After school Marci became an apprentice electrician. Her grandfather took her to the Army Careers Office where she took an aptitude test “… REME came out as one of the top things… you could be a vehicle electrician.

I was like, 'Yeah, cool. I'll do that'.”

Marci was 17 and a half when she enlisted, joining the Women’s Royal Army Corps (WRAC) and undertaking 8 weeks’ basic training at Guildford, during which her grandfather passed away.

Understandably upset, Marci broke down and a female colleague gave her a hug.

Her colleague was “marched off and put into jail overnight. I was brought into the office and told that the only reason I wasn't in jail as well is because my grandfather has died… that (this kind of) behaviour wouldn't be tolerated in the British Army.”

Making Choices – being true to herself

Marci’s were the first cohort of female electricians posted to Bielefeld, Germany for trade training. “…we were a bit of a novelty…we had a really good sergeant that looked after us, he quite openly said, 'I've never dealt with women before. This is all new for me'”.

Other fellow soldiers were less welcoming. “But once they got to know you, and you proved yourself that actually … you could fix the same things as they could… then you earned the respect.” Off-duty, some WRACs invented boyfriends to deter those soldiers who were “… trying it on…some of the guys saw it as a bit of a challenge … a couple of girls had fictional boyfriends...it’s almost like you are leading a double life.”

While being openly gay wasn’t a possibility, relationships between serving women did happen “…different things were acceptable…it was ‘Oh the girls are just doing their thing’, and nobody really asked any questions. But you knew, if you got caught, that was it. You’re out. There’s no ifs, buts, maybes about it.”

You can't be gay and be in the army

One day a friend warned Marci that she was about to be investigated. Shortly afterwards, the SIB (Special Investigations Branch) searched Marci’s room. “…they just went through everything. They took pictures of my friends and my family.

They took a Valentine's card from my mum as evidence and questioned me about it later… you felt like a criminal. You felt like you'd done something seriously wrong.”

Marci was taken to the guard room, told her rights and asked if she wanted a representative. She chose her Sergeant Major. He had one piece of advice. ‘Keep your mouth shut. Don't say anything. Let them do all the talking.’

Marci was questioned off-duty activities, photographs, letters and cards with “female- looking” writing. With no concrete evidence against her, she had to be released. She received a written warning and was told “homosexuality wasn’t allowed in the army.”

Marci’s Sergeant Major was clear. “He said, 'You know you've got choices to make, because you know what the law is in the army, you can't be gay and be in the army… it's up to you.’”

Marci questioned whether she could keep leading a double life. When the Bosnia conflict started, and her workshop was deployed without her, it was the final straw. She handed in her notice.

“I felt like I'd been let down. I wanted to be able to say to people, you know, I'm gay, what of it? And I just thought, I can't do that in the army.”I felt like I'd been let down. I wanted to be able to say to people, you know, I'm gay, what of it?

A year after leaving, Marci was living with friends in Kent and regretting her decision.

“I missed it so much…So I went into the careers office in Chatham, and I signed back on…I made my mind up that if I shut my mouth and got on with it …, if I got posted in England, I could go away for weekends and I could be who I wanted to be. No one would know any different.”

By the time she received her posting orders, Marci had second thoughts. “I remembered how the investigation had been, and I'd been speaking to a few of my friends that were still in and (I realised) I could be discharged this time instead of a warning.”

Finding pride again

Marci found a permanent job and stayed in civvy Street. In 2000, the ban on LGBT serving personnel was lifted. Marci recalls: “There was still prejudice…but officially they were allowed to be who they were.”

In 2023, the Etherton Report – an investigation into the prejudice and the mistreatment suffered by the LGBT serving personnel before 2000 – was published. One of the first steps of restitution was to replace berets and cap badges and send each veteran a letter of apology.

“I wanted the apology letter…it’s in a box in my bedroom that I look at every now and again. That gave me a bit of pride back. I’m proud of my army career. I know it was short, but I am very proud of it. For a few years I wasn’t as proud of it as I am now”

Marci’s connection to the Armed Forces continues through her work, as a caseworker for the Royal British Legion’s overseas team. Sometimes she supports LGBTQ+ veterans who served post ban. “I want people to be out at work, feel supported, not be judged, and have the same offers and support available to everybody. And that's why I wanted to be part of the (RBL) LGBTQ+ Network (of which Marci is the co-chair). You know, the end result wasn’t good, but joining the army did me a world of good.”

The Etherton Report also recommended that a national memorial be created to mark the impact on service personnel of the ban. The LGBTQ+ Armed Forces Community Memorial is an imposing metal sculpture of words inspired by the community’s memories and histories and has been unveiled at the National Memorial Arboretum in Staffordshire by HM The King.