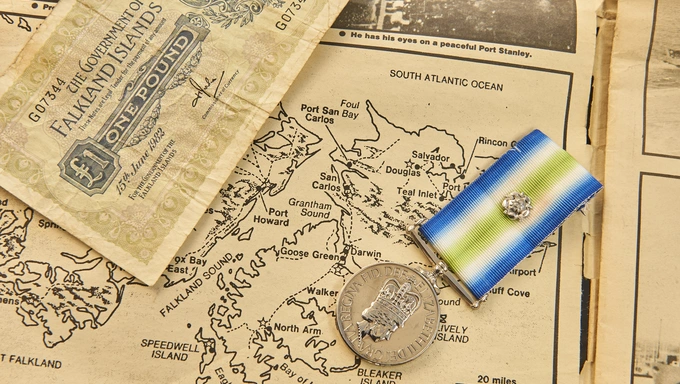

Forty years since the Falklands War, John Sheppard recalls his time as a young chef on board MSV Stena Seaspread during the conflict.

Getting my sea legs

Because I was under 16 I had to spend six months working down an open-cast mine before I signed up, but I knew that wasn’t for me. Only my grandad had any military service, in the Scots Guards.

HMS Raleigh was where I trained, in Torpoint, Cornwall. I got my sea legs in January 1982, when I went on a loan-draft to HMS Penelope.

I was a bit seasick at first but soon got over that and never looked back.

I loved the job – I still look back very fondly at those times. That Easter, I was coming home on leave but got told to grab my stuff and get to Portsmouth, onto a ship heading for the Falkland Islands. I was 17 at the time.

Setting sail for The Falklands

There were about 30 merchant sailors and 160 Royal Navy crew. It was the first big trip I’d had and to be honest, at that age, it was an adventure. We stopped at Ascension Island halfway down, and by the end of April we were on the edge of the conflict.

On the way there, I didn’t appreciate what was happening; the older guys on board probably realised, and were a lot more worried. The work could be testing, lashing things down if the ship was rolling. We were on a 12-hour watch rotation, and I spent a lot of the trip working nights.

Wake-up call

My big wake-up call was when the skipper announced over the tannoy that HMS Sheffield had been sunk by enemy action. I remember the morning when they posted on our noticeboard the ships’ companies that had been lost.

It really hit home to me that this was a proper war when I recognised the name of a lad I’d trained with, and another name, a Leading Cook who’d been in charge of our block at Raleigh.

He’d been drafted onto the frigate Ardent, and died when it was sunk. Seeing those names was a shock. And there was another chef who’d been lost, same age as me, just 17, killed on the Sheffield.

Most people nowadays don’t realise how many chefs died or were wounded during the Falklands War. On the frigates, the galley was under the flight deck, making it a prime target. And on a destroyer like the Sheffield, it was the enemy’s heat-seeking missiles that did the damage, and the galleys are midships – the hottest part of the vessel.

We operated between South Georgia and the exclusion zone. Some of the ships that came alongside us were really badly damaged. I remember HMS Glamorgan – another ship that had been hit in the galley, so that quite a few chefs died on her as well – she had a massive hole in her and had to stay alongside for two days for watertight repair.

Going about my work, I couldn’t be certain that we wouldn’t be next, because we just didn’t know how far outside the zone the attacks were happening.

I think I was probably nervous, but too young to realise it.

In the end, the Seaspread came through it unscathed, and we sailed home a week before my eighteenth birthday, in the middle of August.

Remembering those who never came back

When I got home to the village, it all felt very strange. In those days we always respectfully called the old guys Mister, that’s how we were brought up, and they were all World War Two veterans.

But they just wanted to shake me by the hand, and pat me on the back, even though all I’d done was go there and do my job. That was a surreal time.

For some reason, it’s only in the last few years that I’ve realised what we did, and achieved. I’ve often thought about the lads we left down there who never came back, and I’ve always made sure, wherever I’ve been in my life, there’s a Poppy put down for them on Remembrance Sunday.

But for the Grace of God, as they say… I didn’t know what ship I was going on, and I came back safe and sound. I was able to get married, have children and now, even grandchildren. I’ve had all that, but those lads didn’t have that chance.

We're here to help

.jpg?sfvrsn=fdb9ac44_0&method=CropCropArguments&width=560&height=560&Signature=142CE2BE931FF3665CC80AAC2ACB2D0870B93A6D)