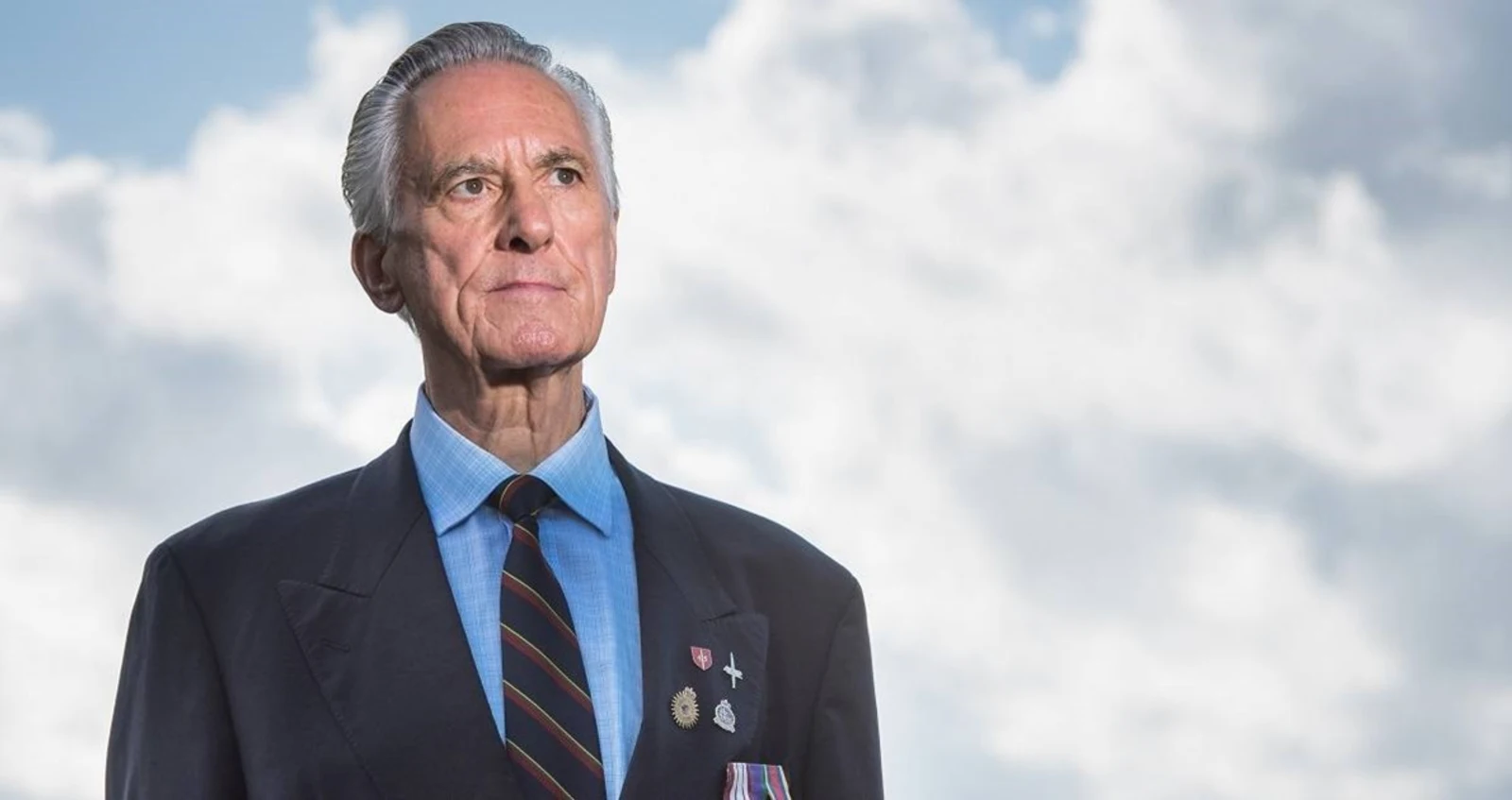

Denis Sparrow joined the Royal Marines as a teenager in 1958, serving for nine years in locations including Aden.

As I approached my eighteenth year in 1957, National Service came to an end. I had been in the Stroud Sea Cadets most of my teenage years, so I had intended to join the Royal Navy, but because it had been discontinued I remained in my employment as a well-paid action fitter in the local piano factory.

The cadets had a magazine, and one edition featured an article about the Royal Marines. After reading and re-reading it several times, I sent away for the forms, and joined up on 28 August 1958.

My training took 11 months, starting with basic fitness and drills but ending with the intense commando training. It was hard but it prepared us for what was to come.

On completion, I was posted to a commando unit just outside Plymouth that was earmarked to go on the first commando helicopter carrier, HMS Bulwark, destination Singapore. That led to my first visit to Aden – we stopped there en route to Malaya and spent several weeks training in the desert.

After hopping around the world, I returned to Aden in 1963, where tensions had began to increase.

Those patrols took us mostly high into the mountains, sometimes as much as 10,000 feet.

Each man would be carrying about 400 rounds of ammunition, four pints of water, rations, grenades… physically, it was quite strenuous. I wouldn’t say there wasn’t any danger, but the marksmen taking potshots at us were a long way off.

Although the weapons they were using were dated, on occasion they were very sharp-eyed, and a friend of mine was killed by one of them.

We also used to patrol districts of the city of Aden, the most dangerous being Crater, which had lots of narrow streets with sharp left and right turns – you could walk into the middle of a riot with no warning just by turning a corner.

We’d patrol a district like that for a couple of months before rotating back up to the mountain border with Yemen.

Our vehicles were continuously attacked and blown up during the hundred-mile Dhala Convoy.

Back in Aden things really got stirred up in December 1963 by a grenade attack on the airport and the government declaring a state of emergency.

The emergency continued with additional added powers until the withdrawal in November 1967. During the January of 1964, 45 Commando – myself included – was sent down to Tanganyika to restore law and order after their army mutinied. It was about that time, after the major operations in the mountains, that terrorism began in Aden itself. During the following years, both areas of operations caused the loss of almost 100 British Service men and women, with around another 500 wounded.

There were also a number of casualties caused by disease, as well as heart attacks brought about by extreme heat and the tough terrains we were patrolling.

My nine-year Royal Marine stint, which had included being inspected by HM the Queen on the lawns of Buckingham Palace and being a member of the Royal Marines Guard of Honour for Churchill’s funeral, finished in September 1967. By then I was married with two children, had a mortgage on a house, and it just felt like the right time to go back to civilian life.

Returning to Yemen

It was nearly 40 years before I went back to Aden. I know a lot of old Royal Marine comrades felt the same as me; that this was a place worth going back to because it had created so many memories. I’d enjoyed meeting Arabs at the time; they’d always seemed extremely friendly to me, with only the odd few causing the problems. So I had warm memories of the place.

I didn’t know what kind of reception we’d receive – my wife, Valerie, was very dubious about going back – and there was even some trouble, with rebels blowing up oil pipelines, during our visit!

But the actual reception we had was absolutely brilliant: word must have got around that all these different British ex-military types were visiting in minibuses, and wherever we drove, local troops and police would stand by the side of the road and salute us. When we returned to the narrow streets of Crater and walked around, civilians came up to shake us by the hand. What surprised me was that it wasn’t just people of our age – those who had lived through the emergency – who were doing this; it was the younger generation too.

When I went back, I took a load of poppies with me and went looking for Royal Marine headstones.

When I went back, I took a load of poppies with me and went looking for Royal Marine headstones in the Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemeteries. A friend who had served with 45 Commando toured the cemetery with me to find every one of them, and between us we put a poppy on each of those headstones.

When I attend Remembrance ceremonies, the memory I have is of going around cemeteries in Aden and looking at the ages carved on those headstones: the 18- and 19-year-olds, several of whom I’d known and served alongside. That was a very emotional moment for me.